This blog post is, in part, a positionality statement and an autoethnographic reflection for my new Political Communication piece, “Scholarly Solidarity: Building an Inclusive Field for Junior and Minority Researchers.” As with all authors, what I write reflects who I am. That includes being a woman, a second-generation Asian-American, a millennial, and a New York native, all things that preceded my academic journey but regularly impact my career. However, for the past 12 years or so, I’ve taken on a professional identity: that of an academic scholar.

As a child of immigrant parents, this was not a profession I knew existed growing up (let alone wanted). This is atypical within the academy, as many academics tend to have parents with a graduate degree. And yet, I took to academia like a duck to water. I liked writing and I liked thinking about society, so a career where I would get to write (and teach and learn) about society made a lot of sense.

However, sticking with an academic career was not only a matter of “fit” (or “ikigai”). And, as I reflected upon my brief academic journey, for both my Scholarly Solidarity piece and for my annual reviews, an important thing dawned on me.

I have been blessed with, by and large, a supportive and welcoming community. This began as early as my undergraduate years, when I worked with Dr. Atsushi Tajima. He took me on as a student even with my abysmal 0.9 GPA (my undergrad GPA remained below 3.0 for my entire time in college). While I do have some horror stories, most of the senior faculty and PI who I work with and learn from are overwhelmingly generous to me, including (but not limited to): Brad Gorham, Hub Brown, Guy Golan, Lew Friedland, Dhavan Shah, Mike Wagner, Doug McLeod, Jon Pevehouse, Talia Stroud, Gina Masullo, and Sharon Strover.

This is not a typical experience for a graduate student. Amazing and brilliant Master’s and Ph.D students are routinely exploited for their labor. In a publish or perish atmosphere, you are encouraged to see potential collaborators as competitors. And the pressures from the academic hierarchy and limited job prospects contribute significantly to poor mental health among academic researchers.

These problem are not limited to grad life: they can be exasperated as a post-doc or junior faculty, who are paid more but are still often exploited for service, or given ambiguous benchmarks to achieve. And of course, such problems are amplified for female and under-represented scholars, not only at these early stages in their career, but throughout their professional careers.

But there’s no reason why it can’t be better. If we want this profession to continue thriving, we need to do a lot more to support one another. This includes prioritizing collaboration over competition, calling out blatant exploitation, supporting researchers who are harassed or threatened, extending grace when possible, and maintaining relationships with people who transition between academic and non-academic positions.

One reason why this matters a lot to me is because I am a young academic. People remind me about this a lot (which, fair, I’m the equivalent of a toddler in the temporal schema of an academic lifespan). But this makes me even more motivated to build solidarity among scholars. If I hope to be in the field for a long time, and I do, I want to work in a profession that is more equitable, thorough, and self-reflexive.

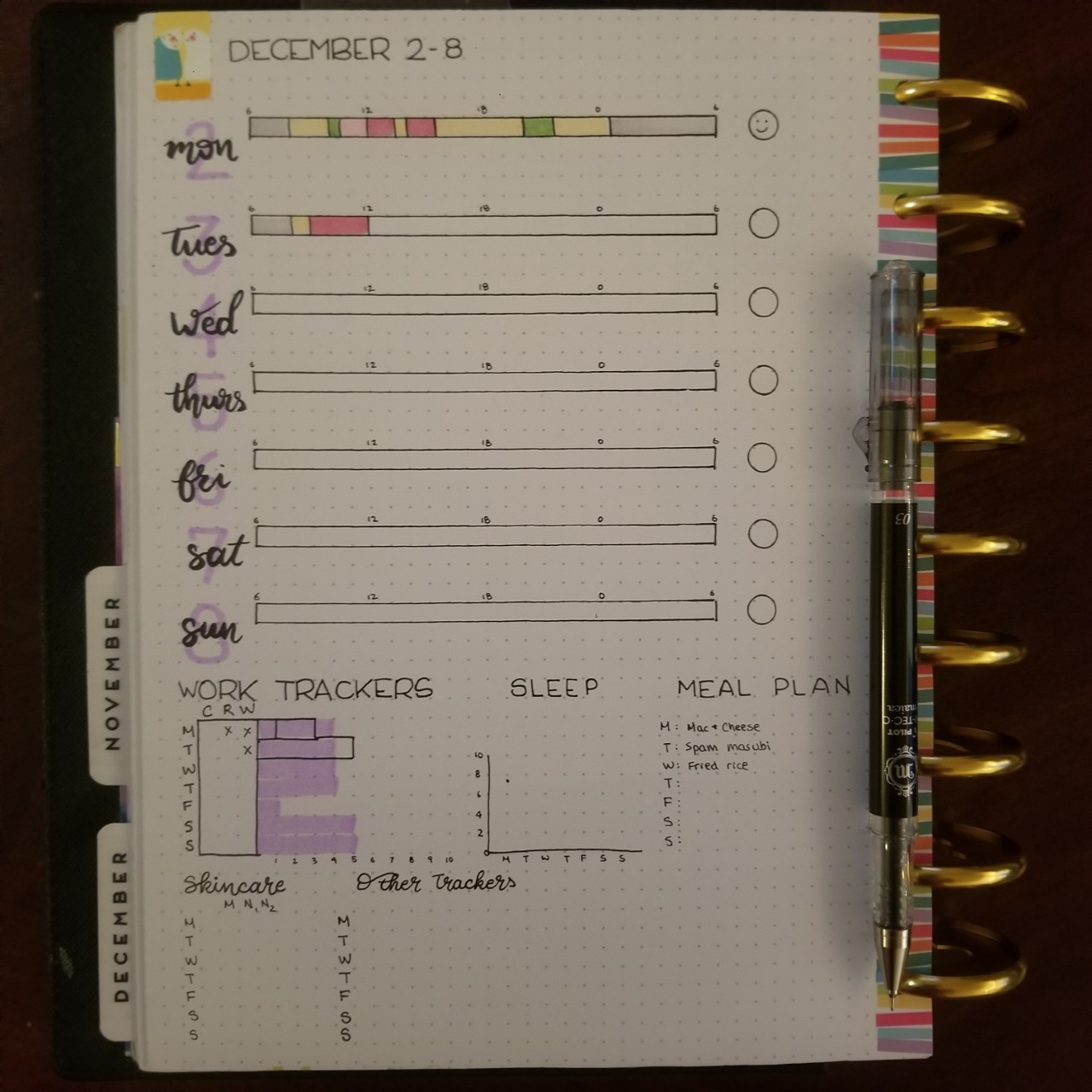

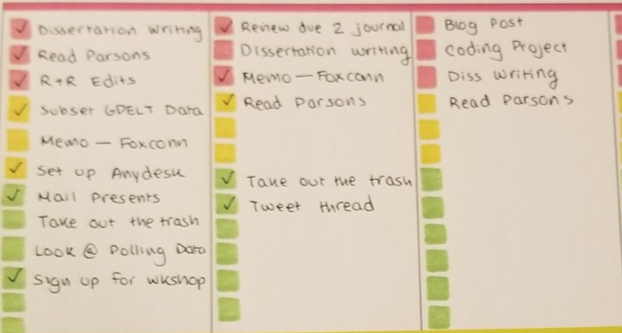

The importance of solidarity and community became all the more important during the COVID-19 Pandemic. I defended and started my Assistant Professorship during the pandemic (August 2020, to be exact). In many ways, I had never felt so alone, professionally and personally. As someone who enjoyed being a part of an academic community, it was frustrating to lose the ability to do that at a critical point in my career: the start of my tenure track clock.

The silver lining of the pandemic for me was the Media and Democracy Data Cooperative. Realizing that there was no difference between being on a zoom call with my students or with my collaborators, I wanted to build a (largely virtual) community of political communication and social media researchers who could support each other both infrastructurally and intellectually. MDDC helped me get a better sense of what scholarly solidarity could look like, and what it meant for researchers to support one another, within and across institutions, for the pursuit of knowledge.

My thoughts on scholarly solidarity are built on these experiences, including minimizing the harm I and many scholars can experience while also maximizing the things I love most about being an academic: doing good research with good people. I am endlessly grateful my many colleagues and collaborators (junior, senior, and non-academic researchers), who inspire and support not only my work and my professional aspirations, but my existence as a human. Thank you for showing me what scholarly solidarity looks like.

![Amazon Product: [Upgraded] Smart Meter Cover RF Radiation Shield | Independently Tested and Shown to Reduce 95-98% RF Radiation from Smart Meters | USA Company](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/573e619937013b2055692e37/1608945833728-S7IU0XMVRRLF7PDGBOP1/review_2.png)